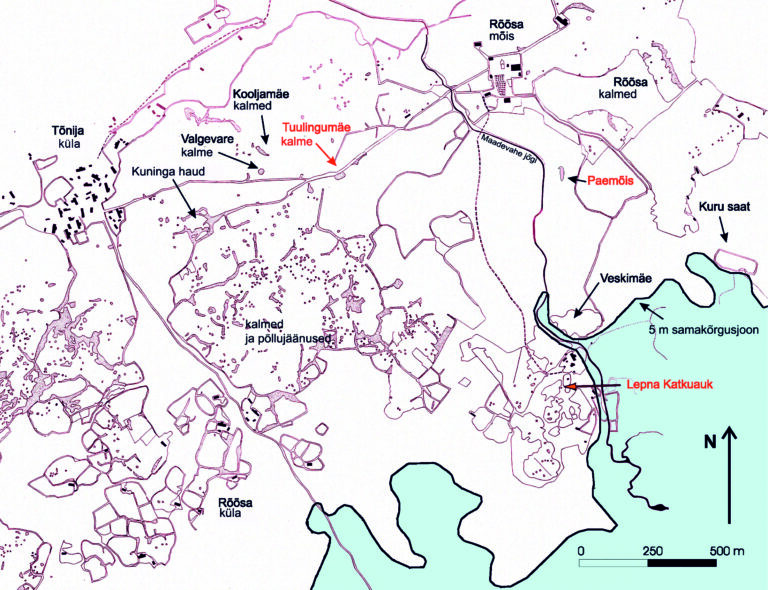

The 2002–2003 archaeological excavations were carried out at a burial ground known in the local tradition as the Lepna Pestilence Hole (Est. Lepna katkuauk). The site is situated near the lower reaches of the Maadevahe River upon an elevation next to the Iron Age coast. As such, it most likely marked the location of a prehistoric harbour site.

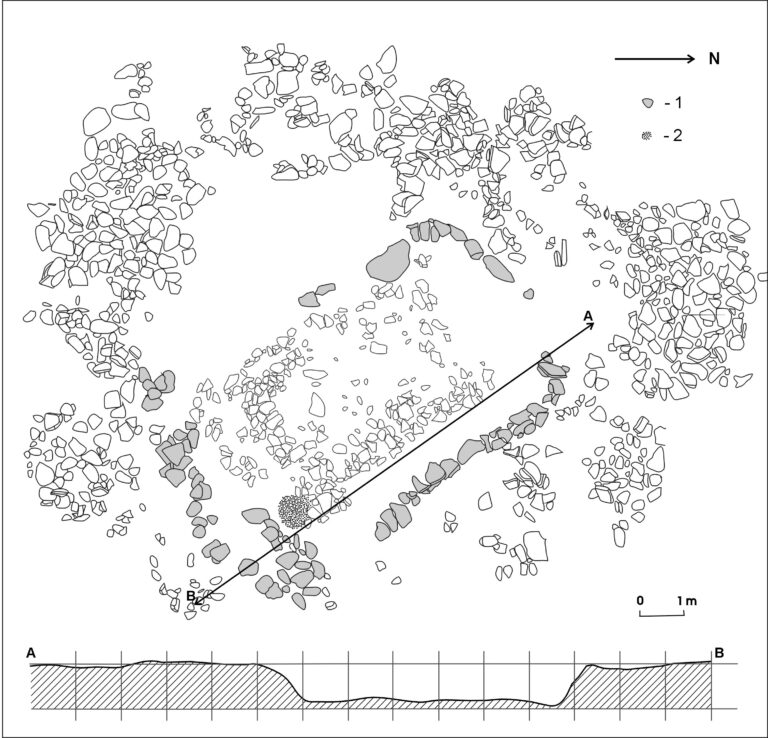

Before the excavations, the “Pestilence Hole” appeared as a hollow overgrown by a thicket. Inhumed human bones were found within the first test pits. The archaeological excavation uncovered the whole area with finds present, and part of the surrounding zone which proved empty. As it turned out, most of the artefacts were deposited inside the remains of a pit-house – the rectangular depression in the ground measured 8.8 x 5.3 m, and was 80 cm in depth. Most of the bones and artefacts came from the same depression, or from its immediate proximity.

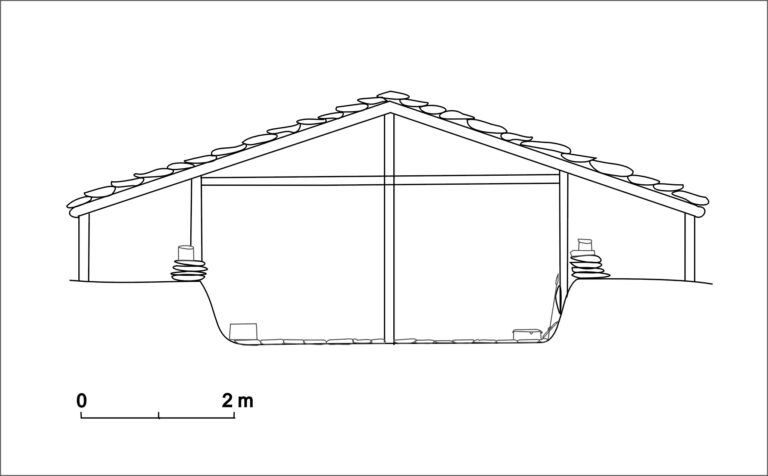

The depression was surrounded by a low drywall of limestone slabs sloping at both ends – these were probably entrances. One corner revealed a location of the post and another, a fireplace. The corner of the depression around the fireplace was lined with clay. The bottom of the pit was covered with a well-preserved flooring of limestone slabs.

At a distance of about 1–1.5 metres, the depression of the building was surrounded by a belt of collapsed limestone slabs, most likely the remains of the building’s roof. The thin slabs had fallen under the eaves, inside the house, and around the depression. A similar medieval pit-building – albeit one without a stone roof – has been excavated at Angerja, Northern Estonia.

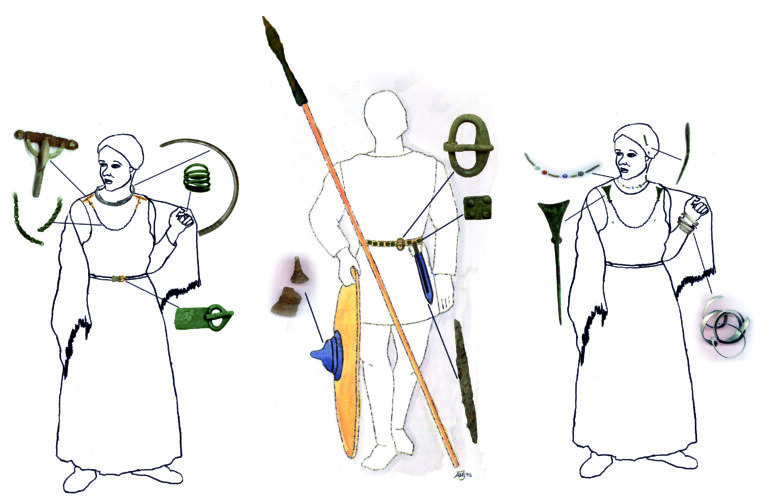

Artefacts recorded in the Lepna mortuary house were abundant: jewellery (pieces of several dozen penannular brooches, neck rings, triangular-headed pins, spiral rings, etc.), as well as belt fittings and weapons. A large portion of the jewellery was made of silver, or plated with silver or gold. Iron was poorly preserved, presumably because the items were exposed to the elements for a long time. Among the iron fragments, pieces of socketed spearheads, shield bosses, and scramasaxes could be identified. Most of the artefacts can be dated to the 6th (or 5th–7th) century, while the six radiocarbon analyses taken from the bones indicated the period between the years 400 and 550.

The human bones were unburnt, but fragmentary and completely intermingled. The site yielded bones of at least 25 individuals, five of them children. Additionally, at least one individual had been cremated (Niinesalu 2020). It seems likely that the human remains belonged to one family.

14C samples from the charcoal taken from the fireplace were dated to the 13th–14th centuries. Seeing as the remains of the collapsed foundation and roof slabs were located upon the fireplace, the building must have stood until medieval times. However, as far as is known, no burials were added after the 6th (or perhaps 7th) century. The long period of being exposed to the elements can explain the fragmentary condition of the bones and artefacts.